|

| Silver hunger-strike medal presented to the Suffragette prisoner Lady Constance Lytton, October 1909 |

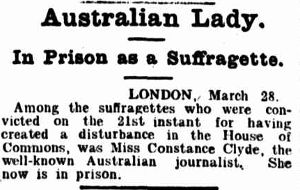

The subject isConstance Clyde, who was born in Scotland in 1872, moved to New Zealand as a child, and then on to Sydney in 1898. She wrote for the Sydney Bulletin, and penned the novel A Pagan's Love, in which ‘questions of women's dependence were raised, with the heroine considering an extra-marital relationship with a man’. As a reporter, she was imprisoned in England in 1907 as one of the suffragettes who ‘caused a disturbance’ in the House of Commons. A similar protest scene was depicted in the inspiring 2015 movie Suffragette. Clyde wrote of some her experiences as a protester in this 1907 article.

She also provided this excellent account of her time in London's Holloway Prison that year.

In 1935 she was living in Brisbane and was arrested for earning money by fortune-telling with tea-leaves. She characteristically refused to pay the fine and was sent to the Female Division at Boggo Road, which at that time was a small timber dormitory next to the main prison off Annerley Road. Upon her release she told the local Press of her time inside there:

'WOMAN TELLS OF EXPERIENCES IN BOGGO-ROAD.

Little Colony That Is Forgotten

Forgotten women in an isolated colony in the heart of Brisbane is how an elderly woman, and a remarkable personality herself, views the women's section of Boggo-road Gaol, in which she recently spent three weeks. Her offence was fortune-telling with tea-leaves, and she refused to pay the fine.

She is ‘Constance Clyde,’ and is well-known by that name to readers of women's periodicals in Australia. Author of a novel, contributor to high-class English reviews, sometime social editress of a Christchurch (N.Z.) newspaper, and in 1906 one of Emmeline Pankhurst's Suffragettes, she indicts Boggo-road as a bleached version of what a woman's prison should be.

She is ‘Constance Clyde,’ and is well-known by that name to readers of women's periodicals in Australia. Author of a novel, contributor to high-class English reviews, sometime social editress of a Christchurch (N.Z.) newspaper, and in 1906 one of Emmeline Pankhurst's Suffragettes, she indicts Boggo-road as a bleached version of what a woman's prison should be.Constance Clyde speaks from experience. In her own words she says that she ‘has experienced several gaols,’ but it ought to be pointed out that since early womanhood she has been something of a stormy petrel in questions affecting feminine reforms. Holloway, one of England's famous gaols, housed her for a couple of weeks, giving her her first taste of prison life.

Although born in Scotland, she was brought to New Zealand at an early age, and returned in 1906 in time to become enthusiastic in the cause of women's suffrage. Mrs. Pankhurst and her famous daughters had espoused action where talk and entreaty had failed and in a still somewhat, conservative age had decided that only by violence could Englishmen be induced to concede Englishwomen their, rightful share in each triennial failure to elect an ideal Commons.

If nowadays the 'average' woman elector votes only under the dutiful pressure of her husband, and the threat of a fine, then it can only be advanced, in extenuation, that times have changed!

Anyway, one of the milder forms of suffragette exhibitionism during 1906 was a proposed gathering of the clan in Parliament Square. The intention of the Suffragettes was to march into Parliament House, and then let Providence be their guide. Miss Clyde was one of them.

On their arrival they found the Square well picketed by policemen, and, recalls Miss Clyde, she was one of about a hundred who were arrested and sentenced to Holloway. They were regarded by their sympathisers as martyrs, and when they came out were given brooches as a memento, the color-scheme being purple and green. This, however, was a mild form of martyrdom compared with those others essayed later by individuals; a peak sensation of the campaign occurred when a suffragette threw herself down, on the race track in the path of the thundering Derby field.

Miss Clyde remembers that as first-class misdemeanants they were given butter in Holloway; they were allowed to retain small personal possessions, such as hairbrushes; they were not denied the spiritual consolation of a minister of religion. None of these advantages, she says, was obtainable In Boggo-road, though the officials were kindness itself.

‘I realise perfectly,’ she said, ‘that a gaol is not intended to be a rest home. But Boggo-road impressed me as being run on a wrong principle. For instance, we were not allowed hairbrushes, but were provided with a big comb each, with which to do our hair 'in a nice, neat bun behind,’ according to framed regulations issued in 1890.’

|

| (Australian Town and Country Journal, 18 November 1903) |

There was not even dripping on the bread, and the food supplied was of a needlessly poor quality, declared Miss Clyde.

The tone of the section was neglect and decay. ‘It is as forgotten,’ she added, 'as an Aztec temple in ancient Peru.’

‘There is no regular weekly inspection, and the doctor to most of us was a rumor. He did not see everyone on entry. No members of women’s organisations, or other organisations, come to console or uplift. Sundays were like other days, without the vestige of a service.

‘On the second of my three Sundays our religious food was one bar of music faintly wafted to us from the men's prison, where the Salvationists held a service. No Salvationist came over to call us ‘sister.’

‘On one weekly evening the men were entertained to an uplift movie. It would have been- easy, as in other prisons, to send the women over to some hidden part of the hall, but we were not sent over.

Prison Clothes.

‘There were two sorts of prison clothes - garments crisply new, and others that crept down. The socks were past redemption. I found difficulty in obtaining from a mouldy Government box a pair of the heelless prison slippers that would stay on my feet.

‘I was seriously informed that if I couldn't find a pair, on no account would I be permitted to approach my suitcase for a pair of my own. Rather must I perambulate cell, veranda and yard, which comprised our ‘run’ in stockinged soles.

‘I 'did not mind this so much - being fairly Bohemian! - but the first pair of long, white garterless socks that I received had only a half a sole to each foot.

‘Completely deprived of our personal possessions, and of crochet and sewing, and unable to write or play games, we would gladly have mended these socks for pastime. But there is only one Government needle, and no mending wool! I admit there is a sewing machine, which is used for Government work.

‘We were not there to occupy ourselves. When Government work failed we loafed around the yard or sat on our backless benches. I spent part of the third day trying to show a fellow prisoner a certain crochet stitch with a piece of stick and some string. We did nothing in our leisure except read the few tattered and ancient stories of the Victorian era, and some American publications.

Gangster Yarns.

‘After our final lock-up at half past four I sat up till lights out at eight o'clock, perusing these gangster yarns, 'My Nine Years in Hell,''How I Became a Dope Fiend,' and other stories suitable for our condition.

‘Out of the 24 leaden-footed hours we spent nearly 17 in our cells. The authorities have forgotten to put stools in the cells. The furnishings comprise a bed, hard as a brick, without wire mattress, and a locker in which to keep simple provisions. When we took in our dinner stew, served in a dog tin, we might eat it sitting on the bed, twisting round to get at our meat on the locker, or give up the struggle and sit on the floor.

‘Our breakfast and tea meal consisted of a mug of tea with dry bread. We were allowed sugar, and our supply of milk was so abundant that to this moment, freedom attained, I have given this fluid a complete miss.

‘In New Zealand the women are given dripping, and also, every week, one pot of jam of a good brand. In Holloway in Suffragette times, misdemeanants at least received butter.

‘With mild malignancy, the Queensland Government did not allow us to buy anything for ourselves. This system is a hangover from the period when prisoners were held to be reformed by semi-starvation.

Kindly Officials.

‘The officials were humane - their kindly way of speaking, so important a matter to the incarcerated, perhaps saves many from a breakdown. But they do not understand. I heard of one declaring that the 'women were happy enough in gaol.' This is not true. We were all, educated or uneducated, always miserable.

‘The glory time is when a new prisoner enters. From her comes the news - but it is always underworld news. We were not permitted to hear real world news to counteract this evil. It would corrupt us to hear that Bishop so-and-so has laid a foundation stone, or that someone rescued someone else bravely from drowning at Sandgate. Only the evil of the world is permitted to come in.

‘I learned in this gaol how to make 'pinkie,' the names of a few Brisbane gangsters, and how possibly (if I want it) I might, after some hunting, obtain cocaine.

‘An ideal gaol is one that the world remembers, and in which the prisoner forgets. But this woman's gaol is one that the community has forgotten. Only its inmates will remember it and the lessons learnt within its dilapidated walls.’

Official Reply.

When told of ‘Constance Clyde's’ statements, Mr, J. F. Whitney, Comptroller-General of Prisons, said: ‘I would be the last person in the world to claim that the women's gaol is a 1935 model, but the truth of the matter is that there are so very few female prisoners that an expensive building is not warranted.’ He added that the place was perfectly clean and very comfortable, and all the inmates were satisfied with the treatment. ‘Truth’ was taken through the women's prison, and found conditions to be as the superintendent had stated. At present there are five inmates, and all were happily sewing and chatting together.

The building was scrupulously clean; there were five blankets on each bed, and the uniforms worn by the prisoners were neat and clean. Each prisoner, ‘Truth’ was told, is in her cell from 4.30 p.m. till 6.30 a.m. next morning - 14 hours. Visitors are allowed to see inmates frequently, and ‘Constance Clyde,’ the visitors' book showed, had two visitors in three days. A study of the reading matter allowed, revealed no gangster stories.'